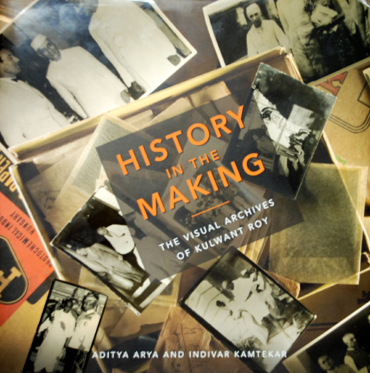

History in the Making: The Visual Archives of Kulwant Roy

By Aditya Arya and Indivar Kamtekar.

HarperCollins.

Pages 304. Rs 4,999.

Reviewed by Roopinder Singh

THE black and white of history, a rare clarity that we get with the perspective of distance in time, a feeling of connection with our past, and the nostalgia that it evokes. This book brings many emotions to the fore as you leaf through pages rich with images of an important moment in India’s history.

Images, à la sauvette or “the decisive moment”, became a modern mantra of photojournalism, in no small measure because it was the title of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s book of 126 photographs, and his long preface that provided the philosophical moorings to his pictures.

I really don’t know if Bresson, widely recognised as the father of photojournalism, met Kulwant Roy during one of his sojourns to India. Roy owned a studio near Delhi’s Mori Gate, and both captured decisive moments in the early history of the Indian nation. Roy was born in Bagli Kalan, near Ludhiana, in 1914. He learnt his craft in Lahore, and later took aerial photographs in the Royal Indian Air Force. The Tribune, then published in Lahore, gave him an early break.

Aditya read History (Hons) at St Stephen’s College, Delhi. He was also a keen photographer, and the secretary of the Photographic Society, of which I was a member too. He lived on the campus, courtesy his father, Dr V. Arya, our Hindi teacher. The lure of being behind the lens was strong enough to make him take up photography as a career, a journey that took him places, professionally and literally.

In a serendipitous moment, Aditya, egged on by his mother, finally opened the trunks left for him by his uncle, Kulwant Roy, a press photographer. Thus, he saw bundles of black and white photographs and negatives that literally made history come alive in front of his eyes.

Here were pictures of Muslim League meetings, INA trials and the signing of the Indian Constitution!

Jawahar Lal Nehru called the Bhakra Nangal Dam a “New Temple of Resurgent India”. Roy took photographs of the construction of this wonder that bring out the human dimension, in the form of thousands of toiling workers, to this infrastructural sculpture in concrete.

As we turn the pages, we see the leaders age in front of our eyes. We notice how they actually mingled with the people … and some incongruities, like the immaculately-clad delegates to the 1945 Simla Conference, being ferried by liveried but barefoot rickshaw pullers. Other feet, however, are clad in contrasting wingtip-brogues, Peshawari chappals, jutti’s and pump shoes worn by various persons in the book.

Different readers will gain various perspectives as they flip through the volume to which has a Foreword by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.

As one browses through it, the feel one gets is of loving and meticulous care that has gone into this book, a design conspicuous by its minimalist approach and elegant touches, like showing the yellowed caption strips in the true yellowed paper they were typed on, Roy’s cameras and so on. Obviously, expenses have not been spared in producing this high-priced book.

Indivar Kamtekar and Aditya have provided the text that showcases this collection. Captioning such pictures would have taken a lot of effort. One wishes for more details, for example, the “Sikh colleague” with Jawaharlal Nehru on page 175 is Partap Singh Kairon, who has figured prominently on other pages of the book too. Some of the princes in the Patiala and East Punjab States Union (PEPSU) pictures, loosely titled as “Phulkian Union”, are misidentified, but these are minor quibbles.

Mention must also be made of the Aditya Arya Archive, which seeks to “digitise, document, annotate and preserve photographic archives in India.” As Aditya says: “Tales of marriage, births, deaths, mourning and celebration captured on film. Photographic archives are an invaluable source of knowledge and interest, our gateway to understanding the past and acquiring a perspective on the present, through diverse visual narratives.”

There were many Roys and each provided his own perspective and eye to recording events as they unfolded in front of his eyes. Of them, only Kulwant, who died in 1984, had an Aditya to turn his sepia bromides into a book that will grace many shelves, and keep alive the memory of the photographer and his work.

The review was published in The Tribune on April 18, 2010