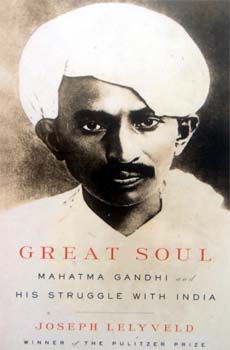

Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and his Struggle with India

By Joseph Lelyveld. Harper Collins. Pages 425. Rs 699.

LONG after he was assassinated, Mahatma Gandhi lives — in the hearts of those who regard him with awe; in the minds of those who read his works and seek to follow his path; on the lips of politicians of all hues, who profess to be his followers; and in the pages of writers and researchers who mine his teachings and life as a part of their literary pursuits.

Joseph Lelyveld is the latest, and by far not the last biographer of the man whose own collected works run into a 100 volumes of around 500 pages each.

“Sage, spokesman, pamphleteer, petitioner, agitator, seer, pilgrim, dietician, nurse and scold (sic)-Gandhi tirelessly inhabited each of these roles until they blended into a recognisable whole,” says Lelyveld even as he follows Gandhi’s footsteps through South Africa to India and England.

Since Gandhi meticulously documented his life, and his thoughts, like other biographers and commentators, Lelyveld has relied heavily on them. With the benefit of having lived in South Africa and India for significant periods of his professional life, he has also explored the making of the Mahatma. He says that it was in 1908, 15 years after he came to South Africa that “the ambitious, transplanted barrister becomes recognisable as the Gandhi who would later be called the Mahatma.”

Those who deify Gandhi often ignore the fact that it took him long years of self exploration, exposure, and grappling with issues to come to the stature of a leader who finally helped to oust the British colonial rulers out of India. Through the book, we see a man who is sensitive to the slights inflicted on him and other Indians by the whites, but not so much to the plight of the majority community in South Africa. After a protest, he expressed indignation at being interned with the native blacks of South Africa. Does this make him a racist or just a human being with flaws? It depends on your point of view, but remember, this is a transitional phase in the life of a person who would truly achieve greatness later.

Many readers will be richer by reading about Gandhi in South Africa, and indeed, the author has treated his subject with inquisitiveness as well as empathy. The book was almost banned before it hit the Indian shores. Credit must be given to the Central government which took a mature stand and has allowed the book to come into the hands of Indian readers.

The controversy regarding the correspondence between Mahatma Gandhi and his German friend Hermann Kallenbach, which has been quoted in the book and innuendos about Gandhi’s sexual orientation, served to pique the reader’s interest to a degree that led to record sales. The letters are there, as is the fact that they had a close bond. Many Indians are comfortable with intense same-sex bonding sans any sexual connotation. Westerners often read it differently, and the author is sensitive to various interpretations.

Overall, during this period, we find Gandhi taking his first tentative steps towards politics, and the ups and downs that come with treading this path. Two telling pictures, one of Gandhi and his wife Kasturba leaving South Africa, and another, besides it, of the two six months later, in Bombay, show the sartorial metamorphosis of the man (three-piece suit to a dhoti-kurta), and reflects the change in his focus.

As for the Indian experience, we have heard it, read it and seen it, but when the author interjects into the narrative, it brings a present tense into the book, which can both be refreshing as well as a bit disconcerting. As we journey across continents with Gandhi and Lelyveld, we go on a journey that is familiar, yet interesting because of twists and turns in the tale, and because of a fresh set of eyes describing the experience.

Gandhi’s greatness does not need any certificates. While it is often stressed that he accomplished much, what is sometimes ignored is his zest for exploring various facets of life. Gandhi was a multi-dimensional personality—he had many quirks, some imperfections and a variety of fads.

Lelyveld joins the rather well-populated ranks of Gandhi biographers. He brings a different perspective, and it is for the readers to either accept or reject his contentions.

We often forget that a book is judged every time it is read. Every reader approaches a book with his or her own perspectives, understanding, background and involvement. Readers will find the journey it takes them along of interest.

The reviewed by Roopinder Singh was published in The Tribune on May 15, 2011