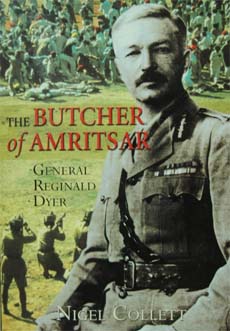

The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer

by Nigel Collett. Rupa. Pages 575. Rs 295.

WE all know him for what he did—butchering civilians at Jallinawala Bagh in 1919—which put him in the hall of infamy the world over and effectively ended his military career. He, however, was not someone who hated Indians; he had, rather, not only been born and brought up in India, but he also spent most of his time with his Indian troops and learnt their languages to communicate better with them.

WE all know him for what he did—butchering civilians at Jallinawala Bagh in 1919—which put him in the hall of infamy the world over and effectively ended his military career. He, however, was not someone who hated Indians; he had, rather, not only been born and brought up in India, but he also spent most of his time with his Indian troops and learnt their languages to communicate better with them.

The British alone have written the two major biographies of Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer; the first was sponsored by his wife, while Dyer was alive, and the latest comes at a time when Dyer has largely been forgotten in Britain.

Nigel Collett is himself a retired Colonel of the British army. Like Dyer, he, too, has served abroad and been fond of writing. Dyer, too, had written a book, Raiders of the Sarhad, which Collett picked up while serving with Balauchi troops.

After three years of labour comes out a book that is huge, but well researched and documented. Collett has gone to original sources where available, and dug up archival material, which makes this an convincing account of the life and times of General Dyer.

He, however, did not have access to most of the correspondence and other material, as it was destroyed after Dyer’s death by Annie, his wife. Collett allows the facts to speak for themselves, even though these are both fascinating and horrifying.

Dyer emerges as a flawed man, much as many other officers of the-then British Indian army, who gave himself too much importance and had scant regard for procedure or even truth. His sojourn in the Persian border area of Sistan and his account of that in Raiders is sufficient evidence of that.

Here’s a story of the British in India, their behaviour, prejudices, what they considered their sense of duty, their interaction with the Indians, their loves, fears and hatred.

Reginald Dyer’s family spent much of its time in India, in the foothills of the Himalayas, at Kasauli, where his father, Peter, set up his first brewery, which was later shifted to Solan. The family lived in Shimla during the heydays of the Raj and Rex, the youngest son, studied at Bishop Cotton School along with his brothers.

Rex’s mother, Mary, was a domineering woman with nine children and ran the house, while Peter’s brewing business kept him very, very busy. After his schooling, Rex was sent to Ireland to study and the dozen or so years that he spent in the UK were certainly not happy. When he returned to India, he was already an officer in the British army who had seen action in Burma.

He served largely on the western frontier, where he sought to distinguish himself by indulging in “heroism”, and in the Punjab. Reading Collett’s reconstruction of those days, we see the emergence of someone who sees himself as a saviour. Couple this with a sense of fear that prevailed following the unrest because of the agitation against the draconian Rowlatt Act and thus there is a situation waiting to explode.

General Dyer’s car had been attacked by agitating mobs in Delhi when he was there on holiday and between Ludhiana and Phillaur when he was returning to Jalandhar. His wife and niece were with him and this, the author says, influenced his subsequent thinking.

When he was sent to Amritsar from Jalandhar, Dyer disabled the safety mechanisms by sidelining civil administrators and assuming control. By that time, the situation had calmed down, but most of the administration behaved as if it were under siege. He used aerial surveillance to spot a crowd near Sutlanwind Gate and forcibly dispersed it. The crowd comprised mourners in a funeral procession of persons killed in firing during a protest on April 10, 1919.

The details of the massacre in Jallianwala Bagh are well known, but the General did not stop at killing over 400 persons assembled for a peaceful protest. He also passed the infamous crawling order for every Indian that entered a lane where an Englishwoman had been assaulted earlier.

He had suspects flogged in public; when they became unconscious, they were revived and flogged again. Bombing the city and firing on crowds from aircraft were also considered, but thankfully, the situation had calmed down by then.

For the British, Dyer became a saviour. He found widespread support in the army and the administration, and even after he was cashiered out, following the Hunter Committee report, he was lionised in Britain. Annie and he continued to perpetuate the legend of the “brave and buff soldier who did his duty as he thought it fit”. That they were largely successful in this endeavour shows the environment of conceit and racism that dominated the British Raj. He got a ceremonial funeral in London.

Dyer was largely forgotten thereafter. It is only after this book has come out that he has reoccupied the mindscape of the British establishment.

Indians will never forget Dyer’s infamy. This book must be read because this is a horror that can’t be forgotten. The book is not as long as it seems, the last 140 pages are just notes and references. Read it, to reacquaint yourself with what the Raj and its instruments were really like.

The review by Roopinder Singh was published in The Tribune on September 11, 2005