Remembering the US Congressman from India

FROM Chhajalwadi, near Amritsar, he went to the Congress of the USA and left a mark that still sets him apart from the many who tried to follow him. In the shadow of the changed situation in America following the September 11 attacks, the focus is again on someone who created history many years ago as persons of Indian origin in America celebrate the 45th swearing-in anniversary of Dalip Singh Saund this weekend.

Dalip Singh was the first Asian American to be elected to the US Congress, not once, but three times! No other American of Indian origin has managed this feat even once so far. But it was a long haul for the son of Natha Singh. Born on September 20, 1899, in Chhajalwadi village near Amritsar, Dalip Singh lived in a joint family, the elders of which were engaged in farming as well as construction business. One of his three brothers was Karnail Singh, who retired as Chairman, Railway Board, in 1962 and whose engineering skills were legendary. Unlike his elder brother, Karnail Singh did not use the family name.

“Dalip Singh was a serious-minded person and interested in public work from an early age. He prevailed upon his parents and made them start a school in the village,” says Anup Singh, Karnail Singh’s son and Saund’s nephew.

Saund studied in a school in Baba Bakala, near Amritsar, and at the Prince of Wales College, Jammu, where he earned his BA degree in mathematics from Panjab University in 1919.

|

|

|

|

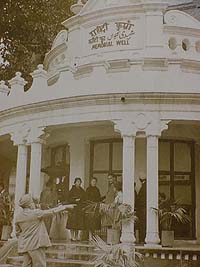

Dalip Singh Saund with Jawaharlal Nehru (L) and J. F. Kennedy (R) |

|

He persuaded his family to help him study in America so that he could learn about food canning and open up an industry in India. “I assured my family that I would study in the United States for at least two and not more than three years and would then return home,” he later recollected in his book Congressman from India (1960).

In 1920, he studied food preservation at the College of Agriculture, University of California, Berkeley, and lived in an accommodation maintained by the oldest gurdwara in the USA — Sikh Temple, Stockton. He also took additional courses in mathematics and later switched to that field, earning first a masters and then a PhD degree. He was active in the Hindustani Association of America and was elected its national president after two years.

|

|

By this time it was 1924 and Saund apparently looked for a teaching assignment, but none was forthcoming and his first job as foreman of a cotton picking gang required no schooling! He also worked in various canning facilities.

“In the summer of 1925, I decided to go to the southern California desert valley and make a living as a farmer.” At this time Dalip Singh was still a turbaned Sikh, though later he became clean shaven.

The farming experience was not an easy one. His first lettuce crop was a financial loss because of overproduction. He also took to selling fertiliser. He found the time to write My Mother India (published by the Stockton Gurdwara in 1930), a rebuttal to Mother India, Catherine Mayo’s blistering attack on India.

Saund had been involved in politics throughout, and Anup Singh says it was on the advice of Madan Mohan Malaviya that Saund left India. The heat from the colonial authorities regarding his ghadar activities was getting too much.

In America, too, Saund kept his public-speaking engagements, whether in gurdwaras or elsewhere, and it was during a talk he gave at Masaryak Club that he met Marian Kosta, the woman who became his life partner.

According to Gurinder Singh Mann, Kapany Professor of Sikh Studies at UC Santa Barbara, Dalip Singh had earlier met Marian “on a ship while travelling from London to New York. In 1928, they married. As an Indian, Saund could not become a U.S. citizen, because a Federal law dating from 1790 declared that only White immigrants were eligible for citizenship. Kosta, although America-born, had to give up her own citizenship to marry him.”

When they met in California, she was a student of the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA). Her father Emil Kosta Sr was an artist who had migrated from Hungry to the USA in 1907. Her brother, Emil Kosta Jr, was a famous Californian painter known for his landscapes. He worked in 20th Century Fox studios as a special effects artist. He won an Oscar in 1963 for his work on the film, Cleopatra, and worked on movies that included Doctor Dolittle, The Sound of Music and John Goldfarb, Please Come Home.

Dalip and Marian Saund had three children. The eldest, Dalip Jr, was born in 1930, followed by his sisters Julie and Ellie. The children were discriminated against. According to an account by author Tom Patterson, a relative of his, Manha Lyall, referred to the children as “half-breeds”.

This has to be seen in the background of the 1920s which was a tough period for immigrants since anti-immigration laws were on the rise. The discriminatory attitude in Westmoreland is held responsible for Marian and the children moving to Los Angeles in 1942, though it is publicly ascribed to an “allergy problem” she had. Marian was a teacher and, incidentally, the children did well for themselves, with Dalip Jr studying mechanical engineering at the California Institute of Technology and doing a doctorate in anthropology from his mother’s alma mater, the UCLA. He was also an officer in the Korean war. Later, he was killed in a flying accident. Julie Fisher and Ellie Ford took to their mother’s profession of teaching after graduation from the UCLA. Julie married a famous oceanographer and has four sons who are living in California. Ellie has two children, a son and a daughter, according to family sources in India.

The passage of the 1946 Luce-Celler Bill marked a watershed in the way the Americans treated immigrants. It liberalised immigration and Saund was one of the early petitioners for citizenship. Till then, though active in politics, Saund could not hold any elected office till he became a citizen, which happened only in 1949.

Talking about the contribution of Saund to the Indian diaspora, Dr I. J. Singh, who went as a Guggenheim Fellow to the USA in 1960 and currently teaches anatomy at New York University, says: “He was a man of principles. He supported the Ghadarites because he supported demands for India’s independence. His contribution to the struggle of Asians for citizenship was strong and memorable.”

|

|

Within a year of becoming a citizen, Saund was elected judge of Justice Court, Westmoreland Judicial District, county of Imperial Valley, but following a lawsuit by local businessmen, he was denied the seat because of a technicality of not having been a citizen for one year when elected.

That there had been resentment about him is obvious from the following anecdote narrated by Saund about his 1952 campaign for the same post:

“One day, just three days before the election, a prominent citizen who was opposing me bitterly saw me one morning in the town restaurant and said in a loud voice: “Doc, tell us, if you’re elected, will you furnish the turbans or will we have to buy them ourselves in order to come to your court?”

“My friend,” I answered, “you know me for a tolerant man. I don’t care what a man has on top of his head. All I’m interested in is what he’s got inside of it.”

“All the customers had a good laugh at that and the story became the talk of the town during the next few days.”

He was elected judge of the same court in 1952 and served until his resignation on January 1, 1957. He is credited with cleaning up the red light district of Westmoreland by awarding stiff fines and jail sentences.

Saund’s eyes were now set on a seat in the Congress. His family, including his son Dalip Jr and daughter-in-law Dorothy Saund, took active part in the intense house- to-house canvassing. After winning the party primary, Dalip Singh was eventually pitched against a Republican candidate, the glamorous and wealthy Jacqueline Cochran Odlum who had been a beauty saloon operator and a pilot.

It was a much-watched fight. Saund was accused of being a “foreigner” and of having been sued by his creditors. Saund successfully negotiated the first issue and explained his position on the second (He had not sought the bankruptcy option that several other farmers had chosen. He had eventually paid off the creditors, something that those who declared bankruptcy did not have to do). He won by 3,300 votes, the first Democrat to have won from the constituency and the first Asian American to do so.

Saund’s fame had already spread and in a rather unusual honour, he was given a seat in the House Foreign Affairs Committee, which would normally have gone to a senior Congressman.

In 1957, he was sent as an official emissary of the House of Representatives, to tour various Asian countries, including Japan, Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, the Philippines and India. Anup Singh recalls that his marriage had been planned to coincide with this visit and the wedding invitations went out in the name of Saund, who was welcomed wherever he went, be it Calcutta, New Delhi, Bombay or various places in Punjab, including his village. “He spoke in beautiful Punjabi,” recall old-timers who heard the Congressman at that time.

Saund was re-elected to the Congress in 1958 and in 1960. But he suffered a severe stroke, as he was preparing to run for the Senate in May, 1962. It left him disabled — he could neither walk, nor speak, but with the devoted attention of his wife, he eventually was able to walk, with the aid of a walker.

The dynamic man who had created history died on April 22, 1973. He is still remembered by many for his devoted contribution to the public life of America and his uncomplaining attitude towards all problems and the discrimination that he faced at various points of his life.

“As we now sometimes face discrimination and harassment — often from mistaken identity — it is good to remember how people like Dalip Singh Saund faced heavier odds and prevailed. When we bemoan the glass ceiling that we encounter sometimes, it would be good for us to recall a young PhD in mathematics toiling on a farm for that was all he was allowed to do. Dalip Singh Saund opened many doors to us. In our success in this multicultural land, we stand on the shoulders of giants like him,” says Dr I. J. Singh.

As Gurinder Singh Mann put it: Saund lived through several phases in the history of Sikhs in America. At the time he began his life in the United States, he could not even become a citizen. By the end of his life, he had not only become a citizen but had taken an active role in the government. His achievements are a landmark in the history not only of Indian but of Asian Immigrants in the U.S. With hard work and commitment to service, one can go very far in the United States of America.

The Tribune, Windows, Saturday, January 12, 2002