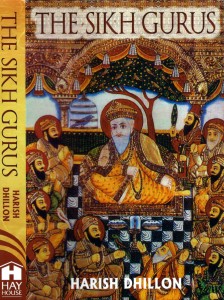

The Sikh Gurus

by Harish Dhillon. Hay House. Pages 294. Rs 499

Review by Roopinder Singh

The founder of Sikhism lived among the common people. He had a family, and after extensive travels that took him far, he settled down in Kartarpur with his wife and children. His successors lived for a century after him, till Guru Gobind Singh decreed that there would be no living guru for the Sikhs thereafter.

The lives of the gurus are fascinating. Various accounts have been written, and these have been narrated by parents to children in an endless cycle. The janamsakhi tradition filled the gap of official accounts of the life of Guru Nanak Dev. Over the years, various historians and biographers have attempted to provide readers with accounts that reflect the extant knowledge about the Gurus and their times.

The lives of the gurus are fascinating. Various accounts have been written, and these have been narrated by parents to children in an endless cycle. The janamsakhi tradition filled the gap of official accounts of the life of Guru Nanak Dev. Over the years, various historians and biographers have attempted to provide readers with accounts that reflect the extant knowledge about the Gurus and their times.

The Sikh Gurus by Harish Dhillon is the latest offering in the genre. The author builds on the work of his predecessors and gives a lucid account. His name is well-known in the region, especially among the readers of The Tribune. He is the author of a number of books, and has built a reputation as an educationist, having headed two of the more prestigious schools in the region.

Dr Dhillon is also a great narrator of tales. He has used his skills to bring alive the lives of the gurus with dialogues and descriptions that his vivid imagination has created from the dry historical accounts. In this, he takes inspiration from the janamsakhis and the vernacular oral tradition.

The world of Guru Nanak comes alive as we turn the pages of the book, we recollect the worry of his parents as he did not fit into the conventional mould, the support he got from Rai Bular, his encounter with a quazi, and his angry response at the looting and plunder of Saidpur by Babur’s army. The author devotes a sizeable chunk of his work to the founder of Sikhism and while all these are familiar stories, these bear re-telling.

His next section deals with the lives of Guru Angad Dev, Guru Amar Das, Guru Ram Das, Guru Arjan Dev, Guru Hargobind, Guru Har Rai, Guru Har Krishan and Guru Tegh Bahadur. Here the author offers succinct accounts, constrained, perhaps, by the fact that in some cases, there is a paucity of material on the lives of these Gurus. We see how the rule of primogeniture was ignored by the gurus in selecting their successors, sometimes to the discomfort of their children.

The life and times of Guru Gobind Singh, however, were extensively documented. He was the last guru of the Sikhs. A towering literary figure who wrote extensively, the guru was also a great warrior. Ballads were sung about episodes from his life. The section on him forms the third part of the book.

The book is not just a historical account; it goes beyond to bring to life the families of the gurus, their wives, sisters, children and relatives who played a part in shaping the history of the region. Bibi Nanki’s love and affection for her brother gave him great emotional strength; Guru Angad Dev’s wife Mata Khivi helped to institutionalise langar; and Guru Tegh Bahadur’s wife Mata Gujri, saw her husband beheaded and grandchildren bricked alive — Sikh women contributed equally in the struggle that the first century of establishing the faith became.

The handsomely produced book has a long and successful history. It was first published as The Lives and Teachings of the Sikh Gurus by UPBPD in 1997 and was re-printed 12 times. A revised version has now been published under a different cover, not-so-coincidentally by the same person who had originally taken the plunge. The cover with a Tanjore-style representation of the 10 Gurus makes the book stand out, although the contemporary paintings, given as insets, strike a different note.

This review was printed in The Tribune on June 21, 2015.