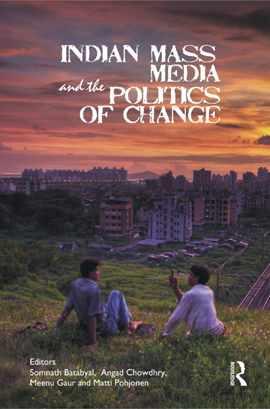

Indian Mass Media and the Politics of Change

Eds Somnath Batabyal, Angad Chowdhry, Meenu Gaur and Matti Pohjonen

Routledge.

Pages 230. Rs 795.

Reviewed by Roopinder Singh

ONCE upon a time, not so long ago, there was a world in which the All-India Radio (AIR) was the only Indian radio service for entertainment. You adventurously tuned into Ceylon to listen to “Binaka Geet Mala”, and for news, which took you beyond government handouts, you tried the BBC. If you graduated to a television, it meant that you tuned into Doordarshan, and before the Asian Games, it was only in black and white. Those of us who lived near the border mounted tremendously tall antennas to garb the signal from Pakistan Television, which had lovely plays and American serials.

Today, Indians are spoilt for choice, but the fare that is dished out by a plethora of sources is the subject of much debate. A group of bright PhD researchers at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London, aided and abetted by their teachers, hosted a conference in 2007 on a theme that has become the title of this book. They invited others to present papers, edited them and today we have them in a book form. It all started with the Sacred Media Cow blog, and along the way came film presentations and much ruminations. They all contributed to the way the content of the book was shaped.

So, you feel that Indian television is broadcasting more news shows than a bulletin of news; editorial roles are being diminished as corporatisation becomes the norm; popular mediums like cinema operate within a narrow band of acceptability, even when presenting themes that are seen as challenging? Linguistic minorities face an uphill task; the proliferation of MMS scandals that exposes the chinks in news mediation; and sex surveys are more about selling than understanding the intricacies of intimacies? If so, then this book provides you with an academic assessment of what, until then, just a gut feeling.

John Hutnyk’s Kali Yuga is of an “over-mighty current affairs presenters, star interviewers, celebrated taking heads, ‘corrupted’ pundits, experts and guests”. Sounds familiar? Somnath Batabyal points out that the “assumed traditional divide between corporate and editorial no longer exists, and news content is aimed at affluent sections of the audience since the advertisers are interested in viewers who can buy their products”.

Meenu Gaur examines the limits of secular nationalism by studying the film Roja. What Ratnakar Tripathy and Jitendra Verma say about Bhojpuri cinema will find a resonance among those who study Punjabi films; minority identities are often in ferment, and find expression in varied ways at different times.

MMS became associated in popular perception with the scandals ever since a school student’s sexual act was recorded and distributed widely, even auctioned on www.bazee.com which led to the arrest of the CEO of the company, which in turn, led to the intervention from the then US Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice. Media pounced upon the incident and further fuelled the craze. Angad Chowdhry examines this and other MMS scandals, and how merely naming these grainy MMS clips after celebrities made them go viral, even after people realise that they are not authentic. The non-institutional, unauthenticated MMSes represent a media not often discussed, even though it warrants our attention.

Kriti Kapila takes us through the world of sex, statistics and surveys and brings out many important points that are often ignored, and concerns about the commodification of women as sex objects, both by the surveys and the media reports that follow them. Though “India Shining” became a beacon for the BJP, the party suffered its poll debacle. At its prime, the image held an allure that was so bright that it now seems inevitable that it turned out to be a mirage.

Angad Chowdhry and Aditya Sarkar have an interesting take on the effect of the past on the present set amidst Mumbai’s labour issues and Barak Obama’s presidential campaign. Soumyadeep Paul and Matti Pohjonen give an engaging account of seeking to understand the early developments of digital media in India, like the blogs that sprang after the Tsunami hit India in 2005, and seek to strike a collaboration between theory and practise, a daunting task at the best of times, more so in the flux that is emerging digital media. Naresh Fernandes sheds light on India that is poor and ignored.

Media is a part of the change that it seeks to portray, and this is a welcome effort to examine its role. The book is academic, therefore, it may limit its readership, which would be a pity, since those who read it will benefit from the author’s observations in various papers.

This book review was published on March 22 in the Spectrum section of The Tribune.