The sanctity of the Golden Temple was violated by individuals who failed to respect the Sikh ethos

Roopinder Singh

Members of SGPC task force and activists of SAD (Amritsar) and other radical Sikh outfits clashing with each other at the Akal Takht in Amritsar on June 6, 2014. Photo by Vishal Kumar

Peaceful, serene, spiritual, sublime…these are some of the adjectives used to describe the Golden Temple in Amritsar. When devotees go there, they do so with a prayer on their lips and humility in their hearts. Harmandar Sahib or the House of God, is where human egos should have no place. Every day a Sikh prays to the Almighty to give him the strength to bear the Will of God with equanimity, even as he asks for the wellbeing of all.

The visual metaphor dominates much of the discourse of the modern world. So, let’s talk of images. The most common image of the Harmandar Sahib is one of the golden building set between the serene sarovar. At a certain time, it was pictures of armed militants and their leaders posing with their weapons inside the complex. Then came another image, of the scarred Akal Takht building, the result of Operation Blue Star. Thirty years later, there was a new one, of Sikhs wielding swords and lathis as a group, said to be of Shiromani Akali Dal (Amritsar) workers, clashed with the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) staff. Swords flashed and ripped the spiritual serenity of the Sikh shrine. Did the individuals who dared to violate the sanctity of the Golden Temple even pause to think of what they were doing? One wonders.

SGPC’s charge

The SGPC has been charged with the administration of Harmandar Sahib, and other Sikh gurdwaras since 1920s. Many sacrifices were made by Sikhs to free the gurdwaras from mahants and give access to one and all.

The Sikh struggle is a saga of bravery and sacrifice. Let’s look at how gurdwaras were liberated. Historically, various gurdwaras were entrusted to mahants, who were to act as custodians. Over generations, they came to regard the gurdwaras as their personal property and even started following practices that were inimical to the Sikhs.

It was in the 1900s that a movement of ordinary Sikhs, provoked by instances of high-handedness at various places, started. As it built up, there were many incidents of confrontation between the Sikhs and the authorities. What stands out is not violence, but the remarkable absence of it as peaceful Sikh protesters took body blows, but did not flinch from their task, and did not raise their hand. This is what gave them and their cause strength.

Guru ka Bagh morcha

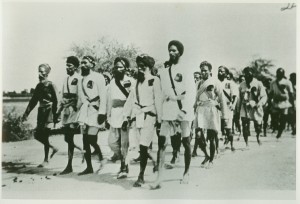

Volunteers marching resolutely to court arrest during the Guru ka Bagh protest. Photo courtesy Panjab Digital Library

Moral superiority was maintained by purity of purpose, strength of spirit and adopting peaceful means of protest. One of the finest examples of this comes from a gurdwara not too far from Harmandar Sahib.

The year was 1922. Groups of Sikhs were protesting against a mahant, Sundar Das, who objected to their collecting firewood from the land which belonged to Guru ka Bagh, a gurdwara. The police and British civil authorities took this to be a property dispute and sided with the mahant. On August 9, 1922, they arrested protesting Sikhs as trespassers.

The SGPC sent more jathas and the police became more and more brutal. Rev. Charles Freer Andrews, a friend of Gandhi who also taught philosophy at St. Stephen’s College, New Delhi, has given a graphic description of how the Akali demonstrators silently prayed even as the police struck them again and again. Their spirit won them worldwide admiration, especially after Andrews’ account was published abroad.

They achieved their purpose when the British authorities finally defused the situation by bringing in Sir Ganga Ram, a wealthy engineer, who on November 17, 1922, acquired on lease the garden land and allowed access to it. Eventually, the British authorities released over 5,000 protesters who had been prisoners.

Clashing images

Some photographs of the protest are now in circulation after being digitised and they provide a poignant reminder, in black and white, of the spirit of the people who struggled to free gurdwaras from the control of hereditary keepers and made them available to the public. The resolute look on the face of those who are about to be beaten up and imprisoned is moving.

Unfortunately, the recent pictures, in print and on TV show how swords flashed in the air and people were injured in the melee that followed. Where was the restraint? Couldn’t the inheritors of the sacrifice of the protesters of Guru ka Bagh have followed their predecessors?

Let the latest incident serve as a trigger for the community to introspect. Looking at the photographs of jathas of Guru ka Bagh protesters marching to court arrests, one remembers the image of their sheathed kirpans, that were not drawn no matter how hard the blows that came their way. They were so strong that they did not resort to violence, did not allow the violence of the other party to move them from the task at hand. The strength of their courage of conviction won the day for them, and immortalised their protest.

Gurdwaras should be places where the mind is without fear and the head bowed low before the Almighty. It is where spirituality should reign supreme. On June 6 this year, this did not happen. A real pity.

CF Andrews’ account of what he saw at Guru ka Bagh Gurdwara on September 12, 1922

Guru ka Bagh protesters beaten senseless by the brutal British police force, but still resolute in their spirit. Photo courtesy Panjab Digital Library

“. . .when I reached the Gurdwara itself, I was struck at once by the absence of excitement such as I had expected to find among so great a crowd of people…”

“Close to the entrance there was a reader of the Scriptures who was holding a very large congregation of worshippers silent as they were seated on the ground before him. In another quarter, there were attendants who were preparing the simple evening meal for the Gurdwara guests by grinding the flour between two large stones. There was no sign that the actual beating had just begun and that the sufferers had already endured the shower of blows.

But when I asked one of the passersby, he told me that the beating was now taking place. On hearing this news, I at once went forward. There were some hundreds present seated on an open piece of ground watching what was going on in front, their faces strained with agony. I watched their faces first of all, before I turned the corner of a building and reached a spot where I could see the beating itself. There was not a cry raised from the spectators, but the lips of very many of them were moving in prayer…..”

“… There were four Akali Sikhs with their black turbans facing a band of about a dozen policemen, including two English officers. They had walked slowly up to the line of the police just before I had arrived and they were standing silently in front of them at about a yard’s distance. They were perfectly still and did not move further forward. Their hands were placed together in prayer and it was clear that they were praying. Then without the slightest provocation on their part, an Englishman lunged forward the head of his lathi (staff) which was bound with brass. He lunged it forward in such a way that his fist which held the staff struck the Akali Sikh, who was praying, just at the collar-bone with great force. It looked the most cowardly blow as I saw it struck….”

“The blow which I saw was sufficient to fell the Akali Sikh and send him to the ground. He rolled over, and slowly got up once more, and faced the same punishment over again. Time after time one of the four who had gone forward was laid prostrate by repeated blows, now from the English officer and now from the police who were under his control. The others were knocked out more quickly. On this and on subsequent occasions the police committed certain acts which were brutal in the extreme. I saw with my own eyes one of these police kick in the stomach of a Sikh who stood helplessly before him. It was a blow so foul that I could hardly restrain myself from crying out aloud and rushing forward. But later on I was to see another act which was, if anything, even fouler still. For when one of the Akali Sikhs had been hurled to the ground and was lying prostrate, a police sepoy stamped with his foot upon him, using his full weight; the foot struck the prostrate man between the neck and the shoulder…”

“The brutality and inhumanity of the whole scene was indescribably increased by the fact that the men who were hit were praying to God and had already taken a vow that they would remain silent and peaceful in word and deed….”

“There has been something far greater in this event than a mere dispute about land and property. It has gone far beyond the technical questions of legal possession or distraint. A new heroism, learnt through suffering, has arisen in the land.

A new lesson in moral warfare has been taught to the world….”

“One thing I have not mentioned which was significant of all that I have written concerning the spirit of the suffering endured. It was very rarely that I witnessed any Akali Singh, who went forward to suffer, finch from a blow when it was struck. Apart from the instinctive and involuntary reaction of the muscles that has the appearance of a slight shrinking back, there was nothing, so far as I can remember, that could be called a deliberate avoidance of the blows struck. The blows were received one by one without resistance and without a sign of fear.”

The turn of events

June 6, 2014. 8.30 am: Bhog of Akhand Path is performed

9 am: Simranjit Singh Mann emerges from Akal Takht and demands a public address system so that he can speak

9.30 am: Mann slips away as his supporters and other radicals get agitated.

9.40 am: Mann’s supporters and some radicals enter Akal Takht and raise slogans. They clash with the SGPC task force with swords

Task force chases radicals. Akal Takht Jathedar appeals for peace. Another clash takes place in the parikarma

Twelve persons are injured in the clash. Twenty eight are booked for attempt to murder and 21 out of those are arrested

This article was published on the OpEd page of The Tribune on June 16, 2014